Cicero’s Aratea

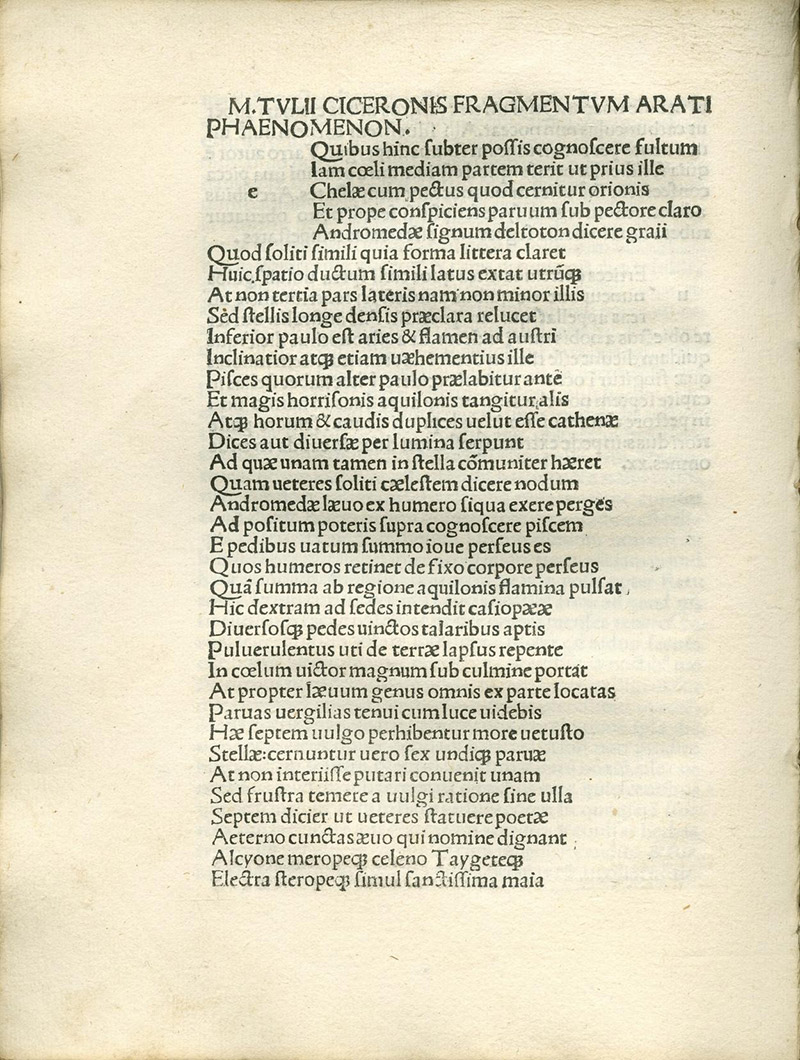

- Cicero, Aratea, lines 1-36.

- Rufius Festus Avienus, Arati phaenomena. Ed: Victor Pisanus. Add: Dionysius Periegetes: De situ orbis (Tr: Avienus). Avienus: Ora maritima. Aratus: Phaenomena (Tr: Germanicus, with comm). Aratus: Phaenomena (Tr: Cicero). Quintus Serenus Sammonicus: Carmen medicinale.

- Venice: Antonius de Strata, de Cremona, 25 Oct. 1488.

Aratus’ Phaenomena enjoyed huge success in Rome. One of the reasons was that it provided an easy account of star lore and basic astronomy in a time when astronomy and astrology became increasingly important. In addition, whether or not Aratus was himself a Stoic, his poem was considered in line with Stoicism in depicting a sky full of “signs” set in place by a benevolent god. This certainly attracted the attention of many Roman poets, as Stoicism was the leading philosophy among Roman elites. Such popularity resulted in a series of translations and free adaptations. Cicero (106–43 BCE), Varro of Atax (b. 82 BCE), Germanicus (15 BCE–19 CE), and Avienus (ca. 305–post 360 CE) translated all or part of the Phaenomena. In the early first century CE Manilius composed his Astronomica, an astrological poem in five books; in the first book Manilius follows Aratus in his description of the constellations and celestial circles (Astron. 1.255-808), even if he adds many more mythological details and does not use Aratus alone as a source for astronomical data. Last of all, in the eight century an anonymous Latin version, the so-called Aratus Latinus, was composed, probably in France. It became very popular, but the Latin is often gibberish because the translator did not know Greek well enough.

We have very little of the Ephemeris of Varro of Atax, a translation of the second part of Aratus’ Phaenomena, on weather signs. The earliest translation of Aratus in Rome is much better preserved; it was made by Cicero, the most important Roman orator and also a distinguished politician during the time of the civil wars. Cicero also wrote many works on philosophical subjects and some poetry; of his translation of Aratus, which he composed when he was young in ca. 90-89 BCE, only 480 lines (corresponding to Aratus, Phaen. 229-701) are preserved by the manuscript tradition; we also have additional 73 lines (of which 8 are incomplete hexameters) in 34 fragments quoted by Cicero himself in his own other works (esp. De natura deorum).

The image shows the beginning of Cicero’s translation from a 1488 edition also containing the translations of Germanicus and Avienus. Cicero translates Aratus faithfully, with little innovation. Yet he sometimes adds some “linguistic notes” about the difference of names between the Greek and Latin constellations; for example, in lines 5-6 of this page, he clearly specifies that the name Deltoton for the constellation of the Triangle is a Greek name, derived from the letter delta (Deltoton dicere Grai / Quod soliti, simili quia forma littera claret). However, Cicero sometimes makes mistakes or omits details in his translation due to his lack of astronomical expertise (even if, ironically, he accuses Aratus of being “ignorant in astronomy” in De Or. 1.69). On the other hand, his translation is rich in decorative details absent from the original and has longer descriptions.

In composing his Aratea Cicero may have also used ancient commentaries on Aratus, as some of his deviations from or additions to Aratus’ poem seems to be reflected in the scholia to Aratus (i.e., marginal notes to Aratus’ poem in medieval manuscripts which derive from the Alexandrian edition of Aratus with commentary). For example, at Phaen. 338-9 Aratus, describing the constellation of the Hare, says: “Beneath both feet of Orion the Hare is chased every single day, constantly.” Cicero’s translation here is slightly different: “Near it [i.e., the Dog] and under the feet of Orion, which we mentioned above, lies the Hare; it flees…” (Arat. 120-121). The detail that the Hare is close to the Dog is not in Aratus but was probably added for clarification in ancient commentaries of Aratus, as we find it in one scholium (Sch. Arat. 338 A): “the arrangement of the stars is good and appropriate, since the Dog, as is appropriate, lies next to the one who hunts with dogs, as his guardian, and the Hare in the chase [is] next to the feet of the one who hunts with dogs”; Cicero might have read the same or a similar note and decided to add this detail to his translation. Similarly, at Phaen. 656-658 Aratus describes Cassiopeia (the mother of Andromeda who was punished because she flaunted her beauty against the gods) and says: “but she sets on her head like a tumbler, taking her share of her knees, since she was not going to be equal to Doris and Panope without great [penalties]”. The ancient commentators of Aratus felt the need to clarify who Doris and Panope were, since they are not famous mythological characters. Hence, we read in Sch. Arat. 657 C: “since she, Cassiopeia, was not ‘going to be equal to,’ that is, to rival the Nereids concerning beauty without great penalties and punishments” (cf. 657–8). Interestingly in his translation Cicero simply speaks of the Nereids, with whom Cassiopeia tried to compete, as if he was following the easier paraphrase of the ancient commentors: “such is the punishment which propitious Nereids inflict her—with them she dared, as they say, vie for beauty” (Arat. 446-447).

Select Bibliography

- Bishop, Caroline. 2016. “Naming the Roman stars: constellation etymologies in Cicero’s « Aratea » and « De natura deorum ».” Classical Quarterly N. S. 66 (1): 155-171.

- Bishop, Caroline. 2019. Cicero, Greek learning, and the making of a Roman classic. Oxford: Oxford University Press: 41-84.

- Soubiran, Jean. 2002 (pr. éd. 1972). Cicéron, Aratea, Fragments poétiques. Collection des universités de France. Paris: Les Belles Lettres.

- Volk, Katharina. 2009. Manilius and his intellectual background. Oxford - New York: Oxford University Press.