Astrological Medicine

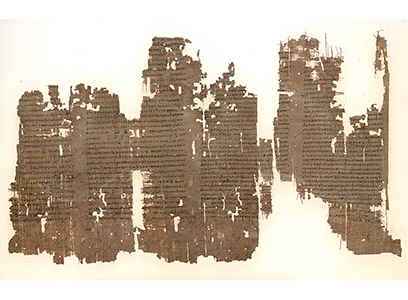

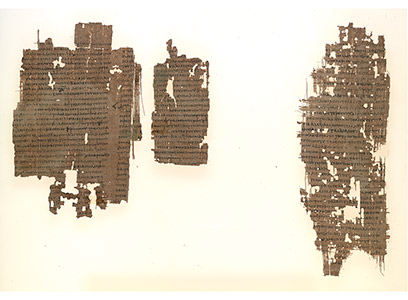

- Planetary Melothesia.

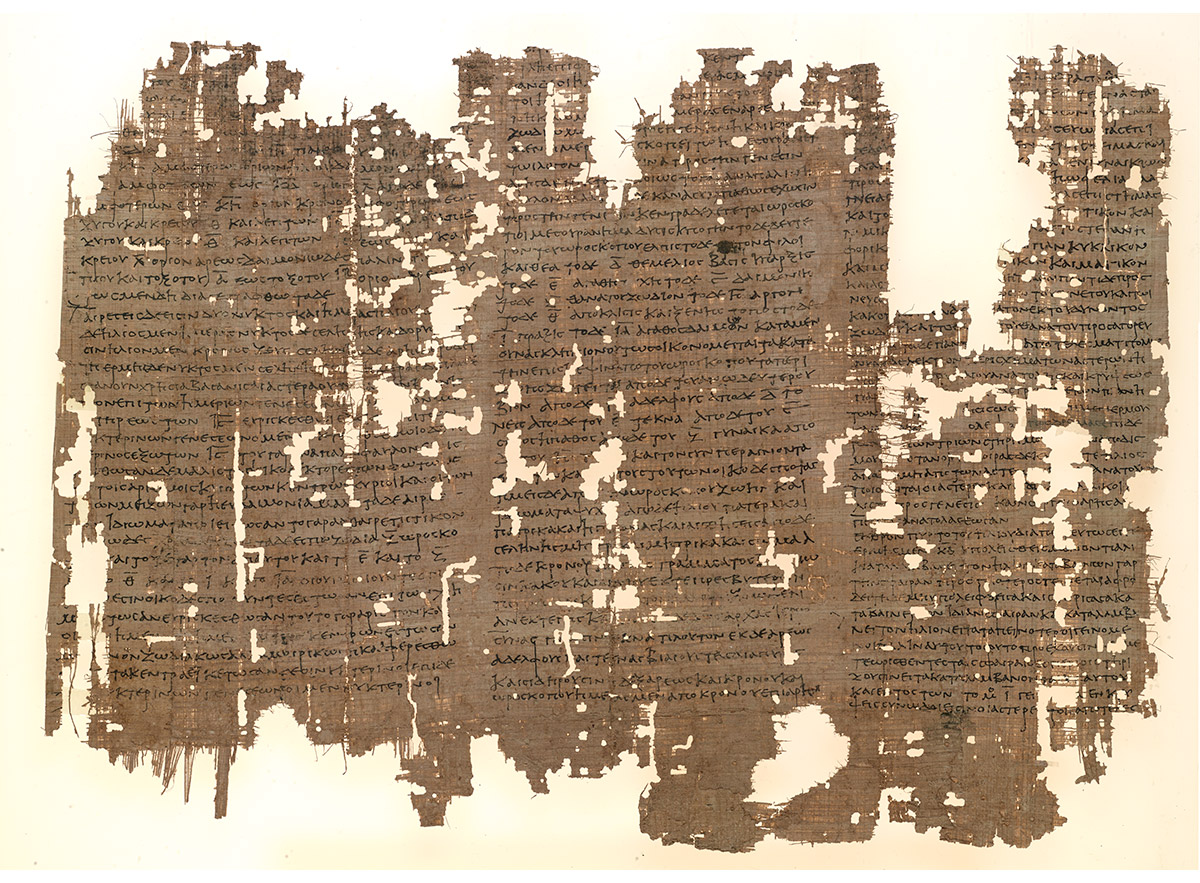

- P. Mich. III 149 = P. Mich. inv. 1, col. i-iv. University of Michigan Library, Papyrology Collection.

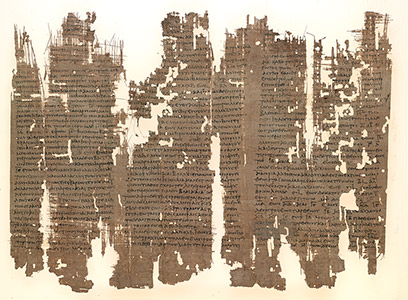

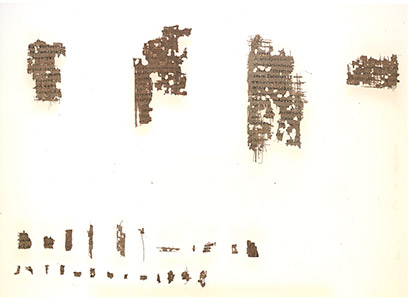

- Planetary Melothesia.

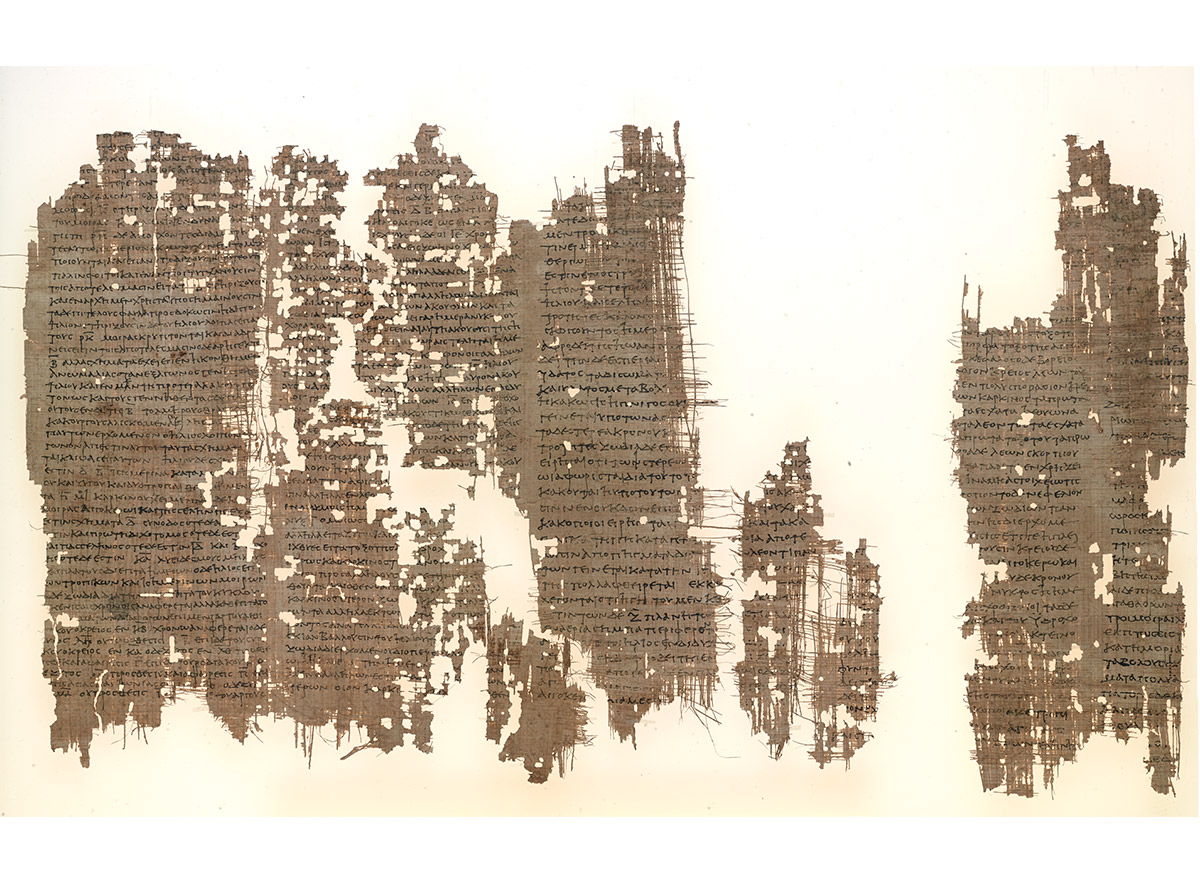

- P. Mich. III 149 = P. Mich. inv. 1, col. v-vii. University of Michigan Library, Papyrology Collection.

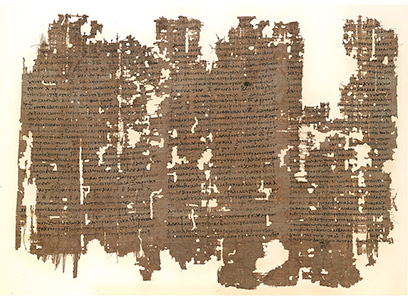

- Planetary Melothesia.

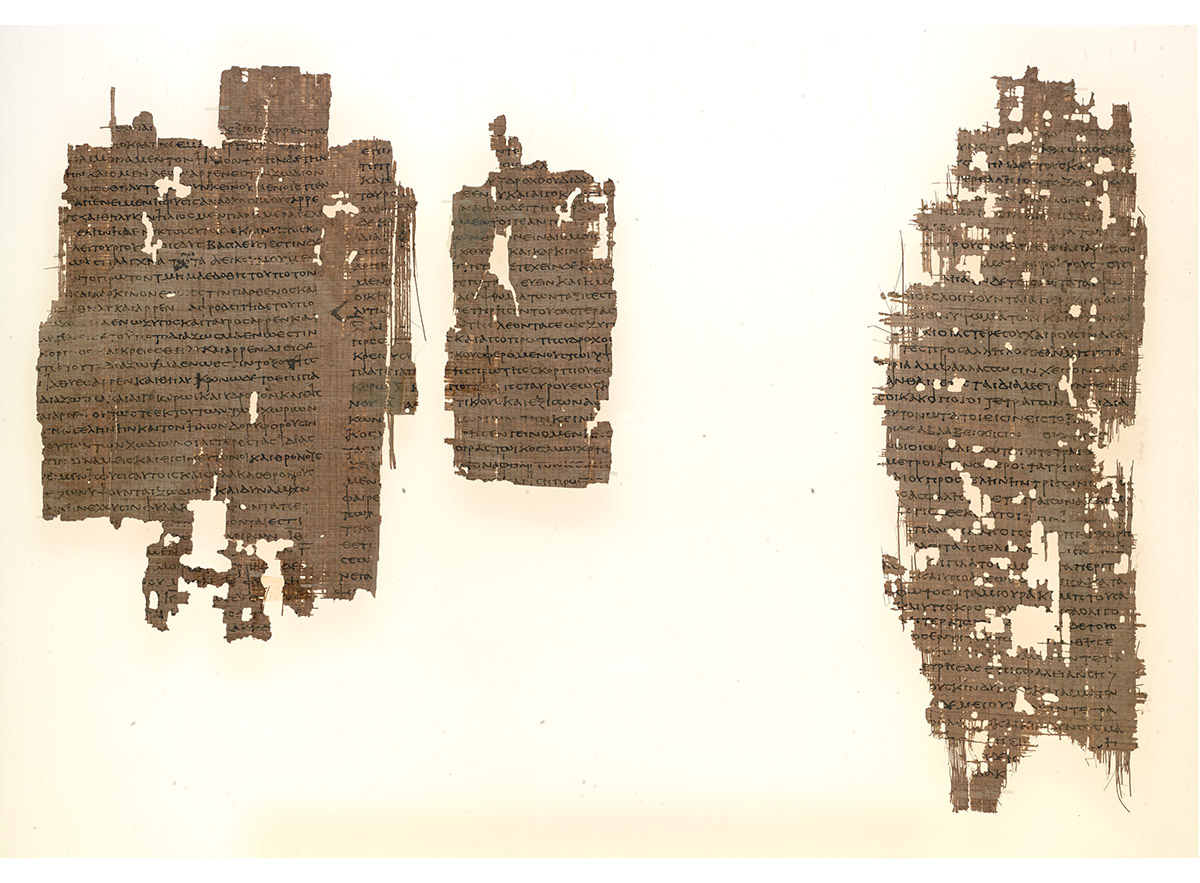

- P. Mich. III 149 = P. Mich. inv. 1, col. viii-x. University of Michigan Library, Papyrology Collection.

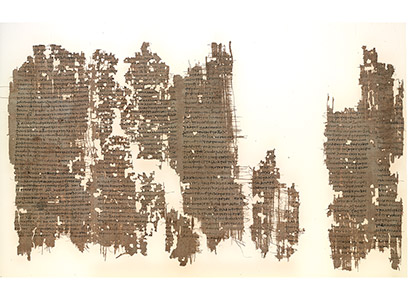

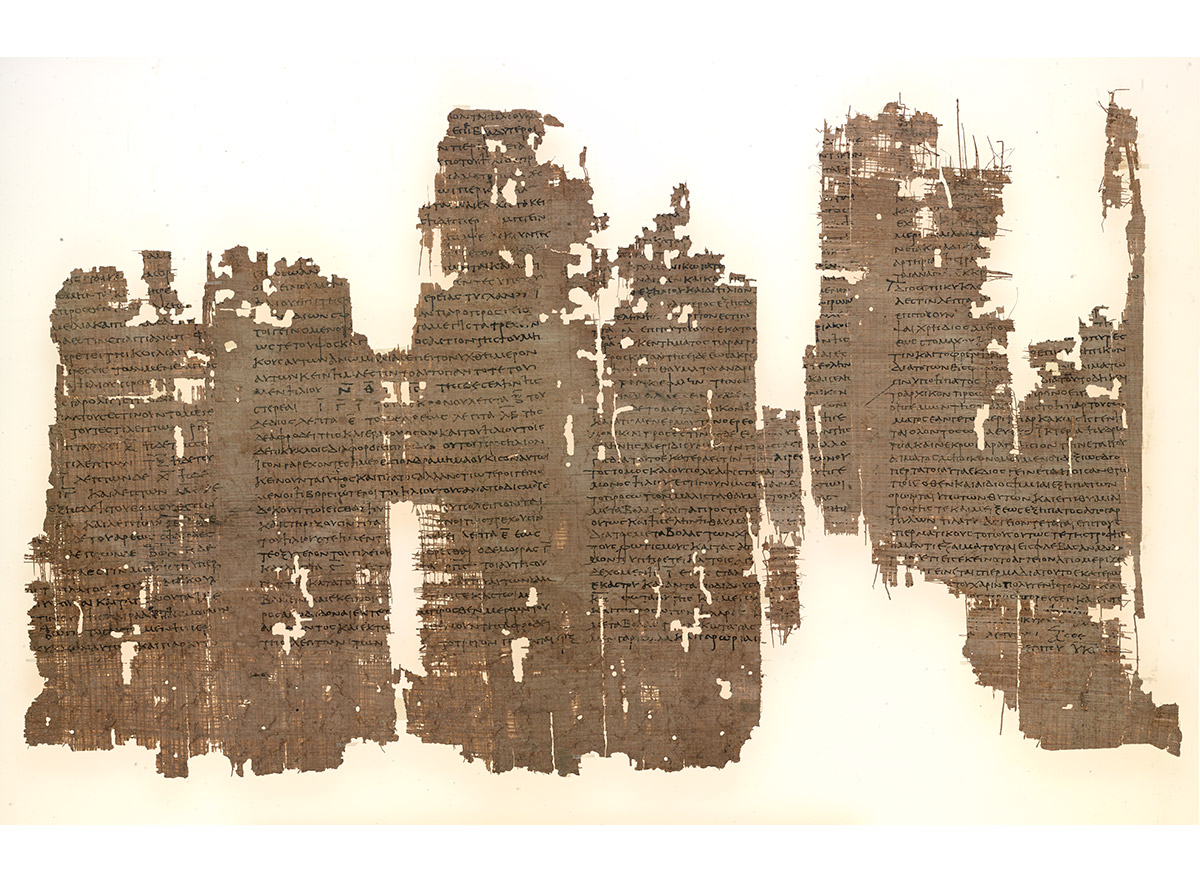

- Planetary Melothesia.

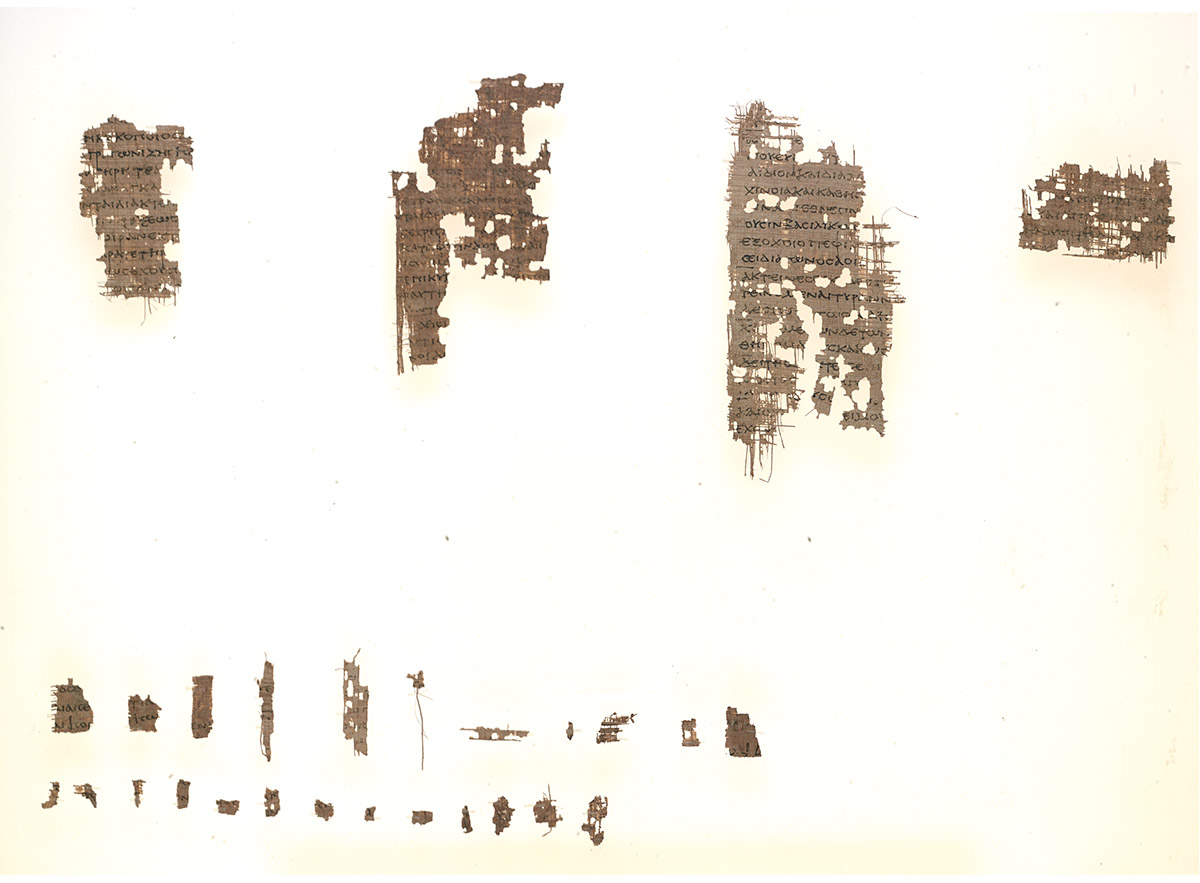

- P. Mich. III 149 = P. Mich. inv. 1, col. xi-xv. University of Michigan Library, Papyrology Collection.

- Planetary Melothesia.

- P. Mich. III 149 = P. Mich. inv. 1, col. xvi-xviii. University of Michigan Library, Papyrology Collection.

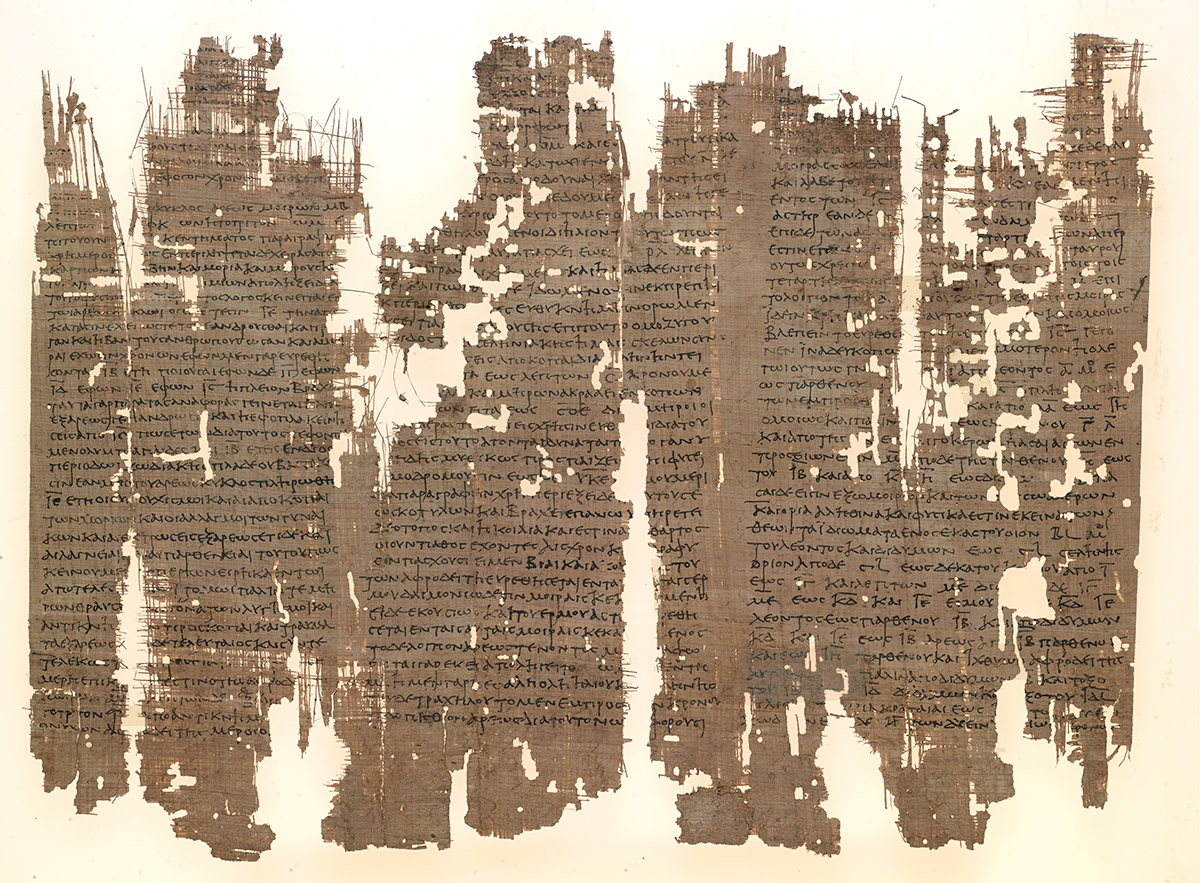

- Planetary Melothesia.

- P. Mich. III 149 = P. Mich. inv. 1, col. xix-xxii. University of Michigan Library, Papyrology Collection.

The papyrus, dated to the second century CE, is a lengthy fragment preserving remnants of 22 columns. The text connects individual planets to parts of the body, a discipline known as “melothesia” (from the Greek melos = limb + thesis = position).

Melothesia, or medical astrology, originated in Babylonian astrology and throve in the Graeco-Roman world. The connection between medicine and astrology is stated also by Ptolemy in the Tetrabiblios (1.2.9, 1.3.13) when he says that both disciplines are conjectural sciences, and both are concerned with prognoses. Ptolemy briefly discusses the effects of planets on us (Tetr. 1.4-5). Porphyry provides a more developed discussion of melothesia in his commentary to the Tetrabiblios (in Ptol. Tetr., 44-45), where he connects body parts with zodiacal signs and planets starting from the head (connected to Aries) all the way to the feet (connected to Pisces).

In medical astrology, prognosis of illnesses was based on the phases of the different heavenly bodies connected with the affected body part; drugs were administered on the basis of cosmic sympathies (something similar to modern homeopathy). While Ptolemy underscores (Tetr. I, 3. 16-17) that medical astrology was developed by the Egyptians, Galen too supported the connection between astrology and medicine to some extent (e.g., On Critical Days, Book 3); in fact, it was Galen’s acceptance of at least the theoretical basis of astrological doctrines that allowed medical astrology to remain part of Galenic medicine until the Middle Ages and beyond.

The papyrus has a planetary melothesia, that is, it connects body parts to specific planets. The distribution of parts of the body (front and back) is as follows:

- Sun = top of head (front); head to neck (back)

- Moon = head to tip of chin, face, tongue, mouth, speech (front); calves (back)

- Saturn = front of throat (front); back of knee, top of thighs (back)

- Jupiter = breast to stomach and liver (front); thighs (back)

- Mercury = ? (lacuna in the papyrus) (front); buttocks to the hip joints (back)

- Mars = hands from the wrists; genitals, thighs, knees, shins (front); to the middle of the neck and back of the neck (back)

- Venus = shins to toes (front); no portion (back)

Interestingly, the author uses the epicycles (developed in the Hellenistic period perhaps by Apollonius of Perga and Hipparchus and then improved upon by Ptolemy to explain planetary motions) and applies them to astrology; even if the theory is not completely correct, it shows a typical aspect of Greek papyri: the mixing of astrology, Babylonian astronomy, and Greek mathematical astronomy. Yet this papyrus is unique in its richness; the anonymous author also shows some independence from the astrological doctrines which we know from other texts.

Select Bibliography

- Robbins, Frank E. 1927. “A New Astrological Treatise: Michigan papyrus Nᵒ 1.” Classical Philology: A Journal Devoted to Research in Classical Antiquity 22: 1-45.

- Robbins, Frank E. in Winter, John Garrett. 1936. Papyri in the University of Michigan Collection III: Miscellaneous Papyri University of Michigan Studies: Humanistic Series. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press: 62-117 [PMich. III 149].

- Neugebauer, Otto, and Henry B. van Hoesen. 1964. “Astrological Papyri and Ostraca. Bibliographical Notes.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 108: 57-72, at 60 [no. 118].

- Neugebauer, Otto. 1972. “Planetary motion in P. Mich. 149.” The Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists 9: 19-22.

- Neugebauer, Otto. 1975. A History of Ancient Mathematical Astronomy. Studies in the History of Mathematics and Physical Sciences. 1. New York: Springer-Verlag: 170–183.